6.1 Append

We shall define an important predicate append/3 whose arguments are all lists. Viewed declaratively, append(L1,L2,L3) will hold when the list L3 is the result of concatenating the lists L1 and L2 together (concatenating means joining the lists together, end to end). For example, if we pose the query

?- append([a,b,c],[1,2,3],[a,b,c,1,2,3]).

or the query

?- append([a,[foo,gibble],c],[1,2,[[],b]],

[a,[foo,gibble],c,1,2,[[],b]).

we will get the response yes. On the other hand, if we pose the query

?- append([a,b,c],[1,2,3],[a,b,c,1,2]).

or the query

?- append([a,b,c],[1,2,3],[1,2,3,a,b,c]).

we will get the answer no.

From a procedural perspective, the most obvious use of append/3 is to concatenate two lists together. We can do this simply by using a variable as the third argument: the query

?- append([a,b,c],[1,2,3],L3).

yields the response

L3 = [a,b,c,1,2,3] yes

But (as we shall soon see) we can also use append/3 to split up a list. In fact, append/3 is a real workhorse. There’s lots we can do with it, and studying it is a good way to gain a better understanding of list processing in Prolog.

Defining append

Here’s how append/3 is defined:

append([],L,L). append([H|T],L2,[H|L3]) :- append(T,L2,L3).

This is a recursive definition. The base case simply says that appending the empty list to any list whatsoever yields that same list, which is obviously true.

But what about the recursive step? This says that when we concatenate a non-empty list [H|T] with a list L2 , we end up with the list whose head is H and whose tail is the result of concatenating T with L2 . It may be useful to think about this definition pictorially:

Input: [ H

∣

T ] +

L2

Result: [ H

∣

T

+

L2

]

T

+

L2

]

But what is the procedural meaning of this definition? What actually goes on when we use append/3 to glue two lists together? Let’s take a detailed look at what happens when we pose the query ?- append([a,b,c],[1,2,3],X) .

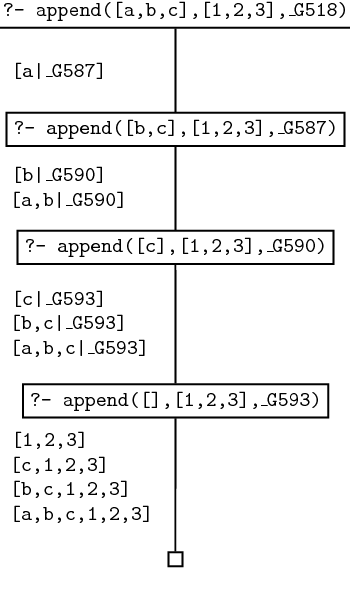

When we pose this query, Prolog will match it to the head of the recursive rule, generating a new internal variable (say _G518 ) in the process. If we carried out a trace of what happens next, we would get something like the following:

append([a, b, c], [1, 2, 3], _G518) append([b, c], [1, 2, 3], _G587) append([c], [1, 2, 3], _G590) append([], [1, 2, 3], _G593) append([], [1, 2, 3], [1, 2, 3]) append([c], [1, 2, 3], [c, 1, 2, 3]) append([b, c], [1, 2, 3], [b, c, 1, 2, 3]) append([a, b, c], [1, 2, 3], [a, b, c, 1, 2, 3]) X = [a, b, c, 1, 2, 3] yes

The basic pattern should be clear: in the first four lines we see that Prolog recurses its way down the list in its first argument until it can apply the base case of the recursive definition. Then, as the next four lines show, it then stepwise ‘fills in’ the result. How is this ‘filling in’ process carried out? By successively instantiating the variables _G593 , _G590 , _G587 , and _G518 . But while it’s important to grasp this basic pattern, it doesn’t tell us all we need to know about the way append/3 works, so let’s dig deeper. Here is the search tree for the query append([a,b,c],[1,2,3],X) . We’ll work carefully through all the steps, making a careful note of what our goals are, and what the variables are instantiated to.

- Goal 1: append([a,b,c],[1,2,3],_G518) . Prolog matches this to the head of the recursive rule (that is, append([H|T],L2,[H|L3]) ). Thus _G518 is unified to [a|L3] , and Prolog has the new goal append([b,c],[1,2,3],L3) . It generates a new variable _G587 for L3 , thus we have that _G518 = [a|_G587] .

- Goal 2: append([b,c],[1,2,3],_G587) . Prolog matches this to the head of the recursive rule, thus _G587 is unified to [b|L3] , and Prolog has the new goal append([c],[1,2,3],L3) . It generates the internal variable _G590 for L3 , thus we have that _G587 = [b|_G590] .

- Goal 3: append([c],[1,2,3],_G590 ). Prolog matches this to the head of the recursive rule, thus _G590 is unified to [c|L3] , and Prolog has the new goal append([],[1,2,3],L3) . It generates the internal variable _G593 for L3 , thus we have that _G590 = [c|_G593] .

- Goal 4: append([],[1,2,3],_G593 ). At last: Prolog can use the base clause (that is, append([],L,L) ). And in the four successive matching steps, Prolog will obtain answers to Goal 4, Goal 3, Goal 2, and Goal 1. Here’s how.

- Answer to Goal 4: append([],[1,2,3],[1,2,3]) . This is because when we match Goal 4 (that is, append([],[1,2,3],_G593) to the base clause, _G593 is unified to [1,2,3] .

- Answer to Goal 3: append([c],[1,2,3],[c,1,2,3]) . Why? Because Goal 3 is append([c],[1,2,3],_G590]) , and _G590 is the list [c|_G593] , and we have just unified _G593 to [1,2,3] . So _G590 is unified to [c,1,2,3] .

- Answer to Goal 2: append([b,c],[1,2,3],[b,c,1,2,3]) . Why? Because Goal 2 is append([b,c],[1,2,3],_G587]) , and _G587 is the list [b|_G590] , and we have just unified _G590 to [c,1,2,3] . So _G587 is unified to [b,c,1,2,3] .

- Answer to Goal 1: append([a,b,c],[1,2,3],[b,c,1,2,3]) . Why? Because Goal 2 is append([a,b,c],[1,2,3],_G518]) , and _G518 is the list [a|_G587] , and we have just unified _G587 to [b,c,1,2,3] . So _G518 is unified to [a,b,c,1,2,3] .

- Thus Prolog now knows how to instantiate X , the original query variable. It tells us that X = [a,b,c,1,2,3] , which is what we want.

Work through this example carefully, and make sure you fully understand the pattern of variable instantiations, namely:

_G518 = [a|_G587]

= [a|[b|_G590]]

= [a|[b|[c|_G593]]]

This type of pattern lies at the heart of the way append/3 works. Moreover, it illustrates a more general theme: the use of unification to build structure. In a nutshell, the recursive calls to append/3 build up this nested pattern of variables which code up the required answer. When Prolog finally instantiates the innermost variable _G593 to [1, 2, 3] , the answer crystallises out, like a snowflake forming around a grain of dust. But it is unification, not magic, that produces the result.

Using append

Now that we understand how append/3 works, let’s see how we can put it to work.

One important use of append/3 is to split up a list into two consecutive lists. For example:

?- append(X,Y,[a,b,c,d]).

X = []

Y = [a,b,c,d] ;

X = [a]

Y = [b,c,d] ;

X = [a,b]

Y = [c,d] ;

X = [a,b,c]

Y = [d] ;

X = [a,b,c,d]

Y = [] ;

no

That is, we give the list we want to split up (here [a,b,c,d] ) to append/3 as the third argument, and we use variables for the first two arguments. Prolog then searches for ways of instantiating the variables to two lists that concatenate to give the third argument, thus splitting up the list in two. Moreover, as this example shows, by backtracking, Prolog can find all possible ways of splitting up a list into two consecutive lists.

This ability means it is easy to define some useful predicates with append/3 . Let’s consider some examples. First, we can define a program which finds prefixes of lists. For example, the prefixes of [a,b,c,d] are [] , [a] , [a,b] , [a,b,c] , and [a,b,c,d] . With the help of append/3 it is straightforward to define a program prefix/2 , whose arguments are both lists, such that prefix(P,L) will hold when P is a prefix of L . Here’s how:

prefix(P,L):- append(P,_,L).

This says that list P is a prefix of list L when there is some list such that L is the result of concatenating P with that list. (We use the anonymous variable since we don’t care what that other list is: we only care that there is some such list or other.) This predicate successfully finds prefixes of lists, and moreover, via backtracking, finds them all:

?- prefix(X,[a,b,c,d]).

X = [] ;

X = [a] ;

X = [a,b] ;

X = [a,b,c] ;

X = [a,b,c,d] ;

no

In a similar fashion, we can define a program which finds suffixes of lists. For example, the suffixes of [a,b,c,d] are [] , [d] , [c,d] , [b,c,d] , and [a,b,c,d] . Again, using append/3 it is easy to define suffix/2 , a predicate whose arguments are both lists, such that suffix(S,L) will hold when S is a suffix of L :

suffix(S,L):- append(_,S,L).

That is, list S is a suffix of list L if there is some list such that L is the result of concatenating that list with S . This predicate successfully finds suffixes of lists, and moreover, via backtracking, finds them all:

?- suffix(X,[a,b,c,d]).

X = [a,b,c,d] ;

X = [b,c,d] ;

X = [c,d] ;

X = [d] ;

X = [] ;

no

Make sure you understand why the results come out in this order.

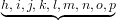

And now it’s very easy to define a program that finds sublists of lists. The sublists of [a,b,c,d] are [] , [a] , [b] , [c] , [d] , [a,b] , [b,c] , [c,d] , [a,b,c] , [b,c,d] , and [a,b,c,d] . A little thought reveals that the sublists of a list L are simply the prefixes of suffixes of L. Think about it pictorially:

Take suffix:

a,b,c,d,e,f,g,

Take prefix:

,m,n,o,p

,m,n,o,p

Result:

h,i,j,k,l

As we already have defined the predicates for producing suffixes and prefixes of lists, we simply define a sublist as:

sublist(SubL,L):- suffix(S,L), prefix(SubL,S).

That is, SubL is a sublist of L if there is some suffix S of L of which SubL is a prefix. This program doesn’t explicitly use append/3 , but of course, under the surface, that’s what’s doing the work for us, as both prefix/2 and suffix/2 are defined using append/3 .